Ngā kauhaurangi Matika maranga

Matika maranga webinars

This is a series of three webinars made for a Ministry of Education professional development and learning programme to support the implementation of Te Whāriki (2017).

Watch:

- Webinar 1: Designing local curriculum

- Webinar 2: Unpacking the goals and learning outcomes

- Webinar 3: Strengthening bicultural practices

A tool designed for use in Matika maranga – a call to action, a Te Whāriki implementation programme.

-

Transcript

Welcome to Webinar 1: Designing local curriculum.

We'll begin with karakia.

Unuhia te pō, te pō whiri mārama

Tomokia te ao, te ao whatu tāngata

Tātai ki runga, tātai ki raro, tātai aho rau

Haumi e, hui e, tāiki e!

From confusion comes understanding

From understanding comes unity

We are interwoven, we are interconnected

Together as one!

Kia ora and welcome to this first in a series of webinars made for a Ministry of Education professional development and learning programme to support the implementation of Te Whāriki (2017).

This webinar series was developed to support curriculum design and includes the following aspects:

- exploring what matters here

- goals and learning outcomes

- assessment and evaluation

- culturally responsive pedagogy

- strengthening bicultural practice.

This webinar, developing local curriculum, focuses on exploring what matters here.

While each webinar can stand alone, the intention is that, together, they represent an holistic view of curriculum design using Te Whāriki.

In this webinar we are going to explain a bit about the programme and how things fit together, but the main focus will be on what learning matters and how we figure that out using Te Whāriki. The kaupapa for this webinar starts with a discussion about being culturally responsive and, as part of that discussion, what place-based learning means – the importance of people, places, and things.

Once we start examining what that means, we move into considering what learning matters to us and for tamariki and their families in our context. The final part of this webinar looks at curriculum design – what used to be called programme planning. Just as Te Whāriki was refreshed in 2017, so too has the way we plan or design learning opportunities for tamariki.

During 2018, ERO released two national evaluations about Te Whāriki – Engaging with Te Whāriki (2017) and Preparedness to implement Te Whāriki 2017.

The bullet points on this slide reflect the intent of Matika maranga. They are also areas for sector-wide development in He Taonga te Tamaiti: Early learning action plan 2019-2029.

Matika maranga is a professional learning programme designed to support a shift from awareness to implementation. Matika maranga is a call to action – to stand up and make a small yet significant change.

As a sector, we love metaphors (like a whāriki) and we love mantras (like learning through play), but sometimes these sit at a high-level and don’t translate into practice. Matika maranga is about practice. Behind that word ‘practice’, sits the creative, intellectual art of teaching and learning. That is what pedagogy means. That is also what ako means, and as kaiako, our role is to be active and to be present both as teachers and learners.

Cultural responsiveness is reflected in what learning matters and your curriculum design. This idea is central to all of our professional responsibilities (whether we are kaiako, whānau, leaders, managers, or owners).

Here we discuss this in relation to what learning matters and leave you with the question: How are you culturally responsive in your curriculum design?

We have an obligation to be bicultural and this is clear throughout Te Whāriki.

This image is in the middle of the book marking the point where the bicultural curriculum meets the curriculum for Kōhanga Reo. Te Whāriki uses this image to illustrate both similarities and differences.

Associate Professor Alex Gunn refers to the potential of this image as symbolising a trusted, sound, situated, localised curriculum with the warp and the weft open for kaiako to weave in their own patterns. This is about what learning matters here – this is about your place, your vision, your philosophy.

Another interpretation is that the older, lighter coloured flax, the old learning, now interweaves with the new learning.

There are also obligations to be culturally responsive in other policy documents like Tātaiako and Tapasā as well as the newly developed Our Code, Our Standards. These all make it clear that kaiako have responsibilities to be knowledgeable, ethical, respectful, and equitable.

Let’s pause here to think about our responsibilities. For example, how have you used the kaiako responsibility card number seven of 15 which says:

[Kaiako are] “able to engage in dialogue with parents, whānau, and communities to understand their priorities for curriculum and learning”?

Part of the conversation about kaiako obligations will be about leadership – leading change; leading through; growing leaders; supporting leaders. We all know that asking about parent aspirations can create some dilemmas, so leadership is important when these discussions take place. We have a strategy to try later on.

What learning matters here? This is not a trick question but it is a philosophical question. This is about your service’s vision for its curriculum whāriki. This is where you define, distinguish, and differentiate your service using Te Whāriki as the basis for discussion.

This is the question that asks you to think about not just what learning matters, but also why, and as part of that, how you weave your own distinct whāriki.

What matters to you? What matters to whānau, to the community, and of course, what matters to tamariki?

Figuring out how to articulate what you believe can be a challenge. Remember, what you believe matters to tamariki in the early years is part of the conversation. Draw on your own personal experiences and bring your professional learning to the table. Think big and small. And document what matters to you as well as finding out what matters to tamariki and to whānau in the context of your community.

There are lots and lots of ideas about how to find out what matters here. We encourage you to watch 5 out of 5; read the Deciding what matters here section on Te Whāriki Online and go back and have another look at the webinar Deciding what matters here, which is also available on Te Whāriki Online. You may also like to watch the video of Dr Anne Meade and Lucy Hayes. The link is under this webinar.

None of this thinking is particularly straightforward – it is complex because we don’t have the same priorities or experiences, or beliefs or values. The role of an early years service is to somehow facilitate a shared understanding about what learning matters to this place, to these tamariki and their families, and to you at this time. That is deciding what learning matters here is dynamic and actually exciting, because we have to respond to context, to what is going on in our lives.

Deciding what learning matters is only part of the answer. The other part concerns how we respond. One of our most controversial but inspiring teachers recognised the importance of place and context to tamariki.

Sylvia Ashton Warner’s writing about working in isolated Māori communities highlighted the irrelevance of the resources and teaching methods promoted in her time – think Janet and John, the early readers for new entrants.

She used the idea of a Key Vocabulary to inspire tamariki to read and write and she noticed that the words they shared with her were those that mattered to them – they were not neutral or uncomplicated. They were real – words like ghost and fight, love, kiss, koro and marae – everyday words that were part of the children’s lives – real, relevant, and rewarding to the communities they lived in.

Another inspiration for understanding the importance of place comes from kaupapa Māori scholars like Wally Penetito and Mason Durie – place is life; place is relationships; place is real.

Wally Penetito’s concept of place-based learning is broad and deep and is an example of relational pedagogy with people, places, and things. You may like to view one of his presentations – you'll see the link under the webinar.

The concept is not solely located in the present. So in the next slide we are going to explore the ideas.

Here is an opportunity to broaden your thinking about place. Bearing in mind what Te Whāriki says, “The expectation is that each early childhood service will use Te Whāriki as a basis for weaving with tamariki, parents, and whānau its own local curriculum of valued learning, taking into consideration also the aspirations and learning priorities of hapū, iwi, and community.” (p. 8)

On the slide you can see some ideas to consider when discussing place-based learning.

Do you know what flora is indigenous in your region? Who planted those old trees?

What do you know about colonisation in your area? What are the stories about your town, your area, your place? Who are your local heroes – past and present? What are the special places in your community and why?

Like we said earlier – a great deal has been written already about deciding what learning matters so in this slide we offer you a different way to think about it.

(Page 14 of the slide PDF.) This model comes from a well known Professor of Law, Laura Lundy, who was concerned that children’s views were overlooked in matters that concern them, and that too often, the grown-ups, like kaiako, made assumptions about what tamariki thought and felt. Each box in the matrix represents an important element of the conversation.

Laura Lundy came up with an idea for us adults to use when considering what matters to tamariki, which can be applied to how we think about what learning matters. For example, the Space box incorporates place-based learning. It alerts us to the physical environment where we hold conversations about what learning matters.

Where do you talk to parents and tamariki? What else is going on? What resources support your conversations about place and learning? Think about the unknown, the spiritual, and the places in between.

Think about Voice: Who speaks? Whose voices are heard? Who is not heard?

Audience is very important: Who do you talk to? Is it the same people all the time? Who is not in the room? What will you do about what you have heard?

This is the Influence box. This is a mechanism for holding you accountable for what you have heard – there is an expectation that you will act on that. And remember: Keep it real, relevant, and rewarding.

Have a go at the Space box. How do you facilitate a discussion about what learning matters to your service? Where do you talk to parents and tamariki? What else is going on in that space? What resources support your conversations about place and learning? And remember, think about the unknown, the spiritual, and the spaces in between.

Talking about what learning matters is a good place to begin thinking about curriculum design, and it's also essential to discussions about Matika, maranga – a call to action.

Curriculum design can be implemented at different layers and levels. For example, immediate application to intentional teaching, for individual tamariki, groups of tamariki, whole of service; short term planning on a focus area; and long range local curriculum planning.

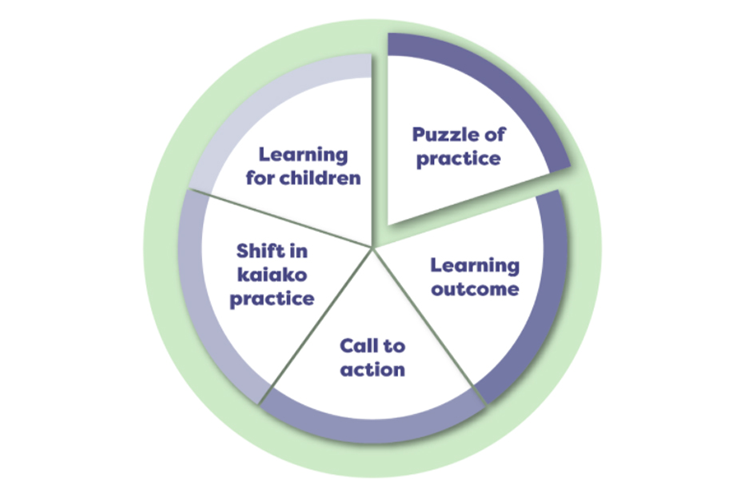

Here is a new way we are thinking about curriculum design using Te Whāriki (2017).

The puzzle of practice concept is a useful way to think about your practice using Te Whāriki. To make it real, we suggest you start with a question about teaching. Then, link this to one or two learning outcomes as a prelude to designing deliberate, intentional, pedagogical actions. Even though the process may be a bit fuzzy or messy, there needs to be discussion about what the call to action might be. Think about that karakia we used at the start of this webinar – unuhia te pō, te pō whiri mārama – from confusion comes understanding, from understanding comes unity.

Remember, even though you are focused on a deliberate, intentional act, keep bringing the learning that matters into your kaiako discussions. Think about the learning that matters as your stepping stone into this process.

Keep what matters here as your pou arahi – your guides. This process complements the other things that are happening in your service, like internal evaluation. Remember it is part of, not over and above!

In the next slide we share an example that highlights the ways the learning that matters becomes embedded in kaiako practices and provides the foundations for curriculum design.

This report He puna reo – He puna oranga whānau was published in June 2018. One of the objectives of the research was to better understand how a kaupapa Māori early childhood education setting (such as Puna Reo) impacts on the health and wellbeing of tamariki and their whānau.

The report reveals how articulating learning that matters translates into a value – he mātāpono – and then becomes embedded in practice. Together with whānau and the health researchers, kaiako interpreted Mason Durie’s Tapa Whā model alongside one of their founding values – kaitiakitanga. Kaitiakitanga or guardianship is a Treaty of Waitangi obligation and also something they use to design curriculum.

Articulating these in their own words underpins the curriculum design of Te Puna Reo o te Kākano. In the next slide, we get a glimpse of how they made it happen.

On this slide (page 23 of the slide PDF), we can see how the kaiako at the Puna Reo created a script, a language for practice that reflects their values – what learning matters to them.

One of their values is kaitiakitanga. The starting point for kaitiakitanga meant prioritising care for the environment. You can see there are some very practical directions under this heading.

Alongside this we can see what kaiako have also thought about mātauranga Māori. There are similar clear, short statements to guide kaiako practices. The practical ideas are calls to action – a useful construct. The links between their values and practice shows how kaiako can make these real, relevant, and rewarding for everyone. This is an example of where to start.

The next slide shows the difference this approach has made to whānau and tamariki. Here is what a whānau member noticed for a child. In this whānau voice, we can see the difference the kaiako have made to that child’s learning and also we get a sense that this is something that also matters to whānau.

“She’s really big into tiaki te taiao and that has totally come from puna. It isn’t something we really push at home. She is really into recycling and telling us what needs to go into each bin, and she is really aware of any kind of rubbish she sees around. And the māra kai, she is right into that as well. We grow some veges at home, so she gets into that.”

Where to from here? Matika maranga, what will your call to action be?

So in summary, we introduced the idea of a puzzle of practice, a question about teaching that is then linked to learning outcomes. Part of any puzzle of practice has to consider what learning matters here. This comes back to the first slide where we talked about how these ideas are all interrelated – another message in our karakia – tātai ki runga, tātai ki raro, tātai aho rau – we are interwoven, interconnected, together as one.

In the next webinar we focus on learning outcomes and identifying calls to action. In this you will be supported to plan a deliberate, intentional, teaching strategy – a call to action that is short and doable.

This brings us to the conclusion of this webinar. And we'll close with our karakia mutunga.

Ka whakairia te tapu

Ka wātea ai te ara

Kia turuki whakataha ai

Kia turuki whakataha ai

Hui e, tāiki e

Mā te wā

-

Resources from webinar 1

Download a PDF version of Webinar 1 slides:

Webinar 1: Designing local curriculum slides (1.5MB)

Anne and Lucy: Deciding what matters here video

Wally Penetito: Place based learning video

-

Transcript

Welcome to webinar 2: Unpacking the goals and learning outcomes.

We'll begin with karakia.

Tūtawa mai i runga

Tūtawa mai i raro

Tūtawa mai i roto

Tūtawa mai i waho

Kia tau ai te mauri tū, te mauri ora ki te katoa

Haumi e, hui e, tāiki e

I summon from above,

I summon from below,

I summon from within and the surrounding environment

The universal vitality and energy to infuse and enrich all present

Unified, connected, and blessed.

This Hawaiian proverb is a call to action.

"A oohe o kahi nana o luna o ka pali; iho mai a lalo nei. Oike i ke au nui ke au iki, he alo a he alo"

The top of the cliff is not the place to look at us; come down here and learn of the big and little currents, face to face

It reminds us that understanding the big picture is one thing but we need to see, hear, and feel what it is like on the ground to be effective.

Kia ora and welcome to the second webinar in a series made for a Ministry of Education professional development and learning programme to support the implementation of Te Whāriki (2017).

This webinar series was developed to support curriculum design and includes the following aspects:

- exploring ‘what matters here’

- goals and learning outcomes

- assessment and evaluation

- culturally responsive pedagogy

- strengthening bicultural practice

This webinar, unpacking the goals and learning outcomes, provides some opportunities to deepen understanding about the why, what, and how of these in relation to your contexts.

While each webinar can stand alone, the intention is that, together, they represent an holistic view of curriculum design using Te Whāriki (2017).

Today we are going to talk about the goals and learning outcomes and your role as kaiako. We’ve got some information to share, some examples and some things for you to think about.

We will explore the goals and learning outcomes in the context of Te Whāriki; highlight the importance of understanding assessment, planning, and evaluation as part of curriculum; the role of kaiako as creative, adaptive, and responsive as they implement a rich curriculum for all tamariki; and, using learning outcomes as a place to start, revisit, and reflect on practice.

Let’s assume that for the most part, your service whāriki is there – all the principles and strands are working together – especially the strands. Most kaiako in Aotearoa can readily cite the principles and strands and, when asked about how they engage or enact Te Whāriki, the most usual responses are to say, “It’s all about relationships.”

“We are doing belonging, or wellbeing, or contribution.”

What we are not so good at is explaining the goals and learning outcomes. We tend to think mid-level to high-level (principles and strands) and that has resulted in most us overlooking the role, the important role, of the goals and learning outcomes.

How you interpret these and then integrate them into your pedagogical practices are what make your service unique. The goals guide your practice and the learning outcomes you plan for tamariki over time are the embodiment of your pedagogy. They are your unique whāriki.

In webinar one we introduced you to the way we are thinking about curriculum design using Te Whāriki. We want you to be bold, brave, and creative in your approach to designing curriculum.

By now, you may be at the stage of trying out some intentional, deliberate acts based on your question about teaching. We have really emphasised the value of linking these actions to one or two learning outcomes.

Before we get into unpacking the goals and learning outcomes, we need to remember that curriculum design, or curriculum planning, includes assessment. They are part of the same conversation. That means that the principles, strands, goals, and learning outcomes are also integral to your overall curriculum design. Remember, the principles and strands are always a happening-thing.

So let’s talk about the goals and learning outcomes.

The potential to enhance curriculum design using the goals and learning outcomes has perhaps been overlooked. There is variability in using the goals and learning outcomes and there are philosophical differences in how we approach outcomes and measurement in the early years.

There are several concerns: First, rather than an open-ended, 'let’s-see-where-this-leads’ approach based on tamariki interests, there can be a fear that pre-set outcomes will somehow restrict and narrow learning opportunities for tamariki. Second, there is a concern that outcomes are an accountability measure as well as a standardised measure for children’s learning and development. The prospect of measurable outcomes is at odds with an early years sector that has a strongly held image of childhood as a time for playing and just being a child. And, finally, as well as that, there is sometimes a fear that our ideas about tamariki and childhood as being a time of relative freedom where spontaneous playfulness is valued may be superseded by formal, structured teaching.

In other words, that learning outcomes represent a product approach to enacting curriculum as opposed to a more open-ended process approach to curriculum design.

Luckily, Te Whāriki is not that sort of curriculum. The biggest, most important learning outcome of all is the aspiration statement in Te Whāriki: “Children are competent and confident learners and communicators, secure in mind, body, and spirit and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society”.

The aspiration is assumed in the image of a whāriki that uses the principles and strands as the warp and weft, and these are the constant backdrop in our early years services. Together with the goals and learning outcomes, they help us make sense of the depth and breadth of the curriculum, a rich curriculum for every child.

A non-prescriptive, open-ended curriculum is a mixed blessing however. That’s because to make it come to life requires conscious, mindful, creative, adaptive kaiako who are prepared to listen; to integrate the professional with the personal; to act in the best interests of the tamariki, their families, whānau, and communities; and finally, to critique their practices in a constant cycle of think, plan, do, and review.

Te Whāriki talks about a split-screen pedagogy. Basically, that means kaiako maintain a dual focus on the how and the what of learning. That means recognising what you can and can’t influence. Our curriculum goals are clear – we can influence the environment where we work and this can certainly impact on children’s learning. What is not controllable are exactly what the learning outcomes will be. Tamariki and their whānau can and will think differently. So will you and your colleagues.

This model can be linked to the think, plan, do, review process in our previous slide. As you think, plan, do, review, you are strengthening your community of learners by sharing what you understand. You are deepening the way you engage in the discussion and slowly creating a community of practice and inquiry. This thinking can be uncertain and uncomfortable and this is why we need to be bold and create safe spaces for our communities to engage.

How does the refreshed, updated version of Te Whāriki help?

Goals, according to Te Whāriki, are for kaiako and therefore are an important element of Matika, maranga. They are implicit in the kaiako responsibility cards. Goals are about what learning is valued in the context of early years service environments. Think back to the first webinar where we talked about learning being real, relevant, and rewarding and also think about instilling in tamariki, a love for the place where they’re living.

In Matika, maranga we have talked about how you, as kaiako or pedagogical leaders, influence the environment.

Let’s break it down a bit.

The focus of the goals, when we think about them, is, in a sense, two fold. They strengthen the role of kaiako and they create a link between the principles and strands, and the learning outcomes.

Staying with that theme – what you can influence – in this slide (page 17 of the slide PDF) we highlight the role of kaiako, the person responsible for making the goals happen. In the column on the left, we have the stem for each goal. As kaiako, no matter what sort of setting you work in, you can influence the environment tamariki experience. In the second column, we see some selected words that preface kaiako responsibility cards. They are ‘doing’ words about what you know, what you value, and how you enact pedagogy.

In the next slide we are going to critique one of the kaiako responsibility cards. Take some time to read this kaiako responsibility card.

"Knowledgeable about and able to try alternative ways to support and progress children's learning and development."

How many alternative ways can we come up with to support and progress children’s learning and development?

Something to consider after this webinar is how you will create the environment for tamariki and others to protect and promote health and wellbeing.

Now let’s think about learning outcomes. Learning outcomes are about knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Children construct knowledge as they make meaning of their worlds, influenced by history, culture, geography, and the people surrounding them. Skills are what children can do and attitudes are about formulating a point of view to express what they think and know and how they feel.

In Te Whāriki it says “knowledge, skills, and attitudes combine as dispositions and working theories” (p. 22), so that means learning outcomes are also about dispositions (the way tamariki approach new learning) and working theories. For example, we know that persisting when it’s difficult, or being curious, are dispositions we can support as tamariki theorise, question, explore, and wonder as they learn and make sense of their worlds. We need to constantly remind ourselves that Te Whāriki presents two world views: te ao Māori and te ao Pākehā. They are not the same.

Te Whāriki prioritises dispositions and working theories in tandem. I quote: “Due to their importance, learning dispositions and working theories are specifically referenced in two learning outcomes.” (This is on page 23)

Recognising and appreciating their own ability to learn︱te rangatiratanga: Contribution, Goal – They are affirmed as individuals. (9/20)

Making sense of their worlds by generating and refining working theories︱te rangahau me te mātauranga: Exploration, Goal – they develop working theories for making sense of the natural, social, physical, and material worlds. (20/20)

In te ao Māori, mana aotūroa is understood as “children see themselves as explorers, able to connect with and care for their own and wider worlds”. In English, the goal states that “children are critical thinkers, problem solvers, and explorers”. What do you think are the implications of these two perspectives when it comes to designing curriculum using the goals and learning outcomes?

All the learning outcomes in Te Whāriki are important. They set out the capabilities that all tamariki need to develop over time. Services choose how these learning outcomes are unpacked in their services and prioritised for specific groups and individuals over time.

Kia whawhati kō means you need to dig in. So in this context, you, as kaiako and pedagogical leaders, choose how to unpack the learning outcomes depending on what learning matters and what you, your colleagues, families, whānau, and community value.

It means taking into account, mana whenuatanga (local iwi land rights), pūrākau (indigenous narratives) and pakiwaitara (local fables, stories), and local tikanga (local iwi customs and practices). It also means making links to the shared history of your place. Implicit in this explanation is how you strengthen bicultural practice. Remember, it’s the how and the what.

Again, in Te Whāriki we find some clear direction about how to use the learning outcomes.

On page 23 it says “The expectation is that kaiako will work with colleagues, children, parents, and whānau to unpack the strands goals and learning outcomes, interpreting these and setting priorities for their particular early childhood setting.” To support kaiako, for every strand there are examples of evidence and practice, and considerations for leadership and organisations, and reflective questions.

There is a lot of valuable information here so it might be worth pausing the recording her and thinking about or discussing the best ways you might get to know these sections as a whole team.

We can’t talk about goals and learning outcomes without talking about assessment. Just as a quick reminder, let’s focus again on the purpose of the learning outcomes and the goals – they’re designed to inform curriculum planning and evaluation, and to support the overall assessment of children’s progress. (Te Whāriki p. 22). They take us back to the space of assessment as part of overall curriculum design.

In the Te Whāriki Online spotlight on assessment, Professor Claire McLachlan talks about how the new learning outcomes impact on assessment by requiring us to organise our practices to both observe in the moment as well as in a planned process to consider children’s learning and development over time.

At the heart of this is the notion of ako – kaiako and akonga. Tamariki are teaching you what to learn, and you are learning what to teach from tamariki. It’s a reciprocal relationship.

Learning outcomes support kaiako to design their curriculum and to intentionally select pedagogical strategy. So when it comes to articulating what matters here, and how to strengthen bicultural practices, the narratives about planning (the how and what of teaching) are as important as the narratives about learning.

In Understanding the Te Whāriki approach, a book by Wendy Lee, Margaret Carr, Brenda Soutar, and Linda Mitchell (2013), there is a planning story for a child about threading where a kaiako identifies some learning outcomes about making patterns and mathematical skills.

An intended outcome in her planning was to stimulate creativity; an unintended outcome – and a bonus – was the leadership the child displayed as she both introduced her friends to threading, and supported them, and, furthermore, revealed her sense of manaaki and whanaungatanga, when she made a necklace for her younger sister.

The point here was that the kaiako was creative and adaptive as she noticed, recognised, and responded to the interest in threading. Over time and with the tamariki, their whānau, and other kaiako the learning lenses on threading widened considerably and threading became part of the curriculum design at Roskill South Kindergarten.

In this Matika, maranga PLD programme we introduced a process to support you to design curriculum – as a way to tell your planning story. We need to consider our puzzles of practice in the context our settings – what are your priorities? What about bicultural practice and what learning matters? Then think about how you organise people, time, materials, and space. As you heard in the example, the learning outcomes need to be interpreted with other kaiako, with and alongside tamariki, family, whānau, and with community, to reflect cultural values, locality, and ideology. Take a moment to read this slide.

Wellbeing

Learning outcome: Keeping themselves healthy and caring for themselves︱te oranga nui (1/20)

Responsibilities of kaiako: Role models for practices that support their own health and wellbeing and that of others (12/15)

Bear in mind, the big call to action: to take into account what learning matters here and the importance of bicultural values. Take a look at the stem: “Over time and with guidance and encouragement”. Again we see how this focuses us on the role of kaiako in children’s lives over time. We need to interpret and, together with tamariki and whānau, set priorities for learning.

Remembering what your responsibilities are, consider the question on this slide. How do you care for your wellbeing and the wellbeing of others? Reflect on how are you role models for wellbeing? How do you reflect hauora, mana atua?

This paper published in 2018 (the reference on the slide: Margaret Carr, Jeanette Clarkin-Phillips, Brenda Soutar, Leanne Clayton, Miria Wipaki, Rea Wipaki-Hawkins, Bronwen Cowie & Shelly Gardner. Young children visiting museums: exhibits, children and teachers co-author the journey, Children’s Geographies, 16:5, 558-570), explored how tamariki and kaiako co-created curriculum based on “a pedagogy of responsive relationships with people, places, and things”. They were interested in how and where dispositions and working theories combine to push learning forward.

The illustration above is Sarah’s “scary dinosaur” drawn during a museum visit. The kaiako reacted to the first drawing with: “Friendly looking dinosaur you’ve got there.” To establish her authority over the story, Sarah contradicted the kaiako and combined her experience of the weight of the dinosaur bone (she had touched a replica in the museum display), a scary dinosaur picture in the museum’s official brochure, and her own ideas about what scary looked like. What was her solution? She added a witch’s hat that revealed her understanding of the cultural significance of witches – who are scary, and so, that made her dinosaur scary.

Co-authoring, argue Carr and her colleagues provided a forum where tamariki, the museum artefacts, and kaiako created new learning possibilities, new interpretations of what learning matters.

So what outcomes sit in this story? We could decide on this one: Overtime and with guidance children will become increasingly capable of making sense of their worlds by generating and refining working theories | te rangahau me te mātauranga. They co-constructed a learning outcome in a dynamic way – in other words, during a shared experience, not afterwards or out of context.

Think about how you could document children’s learning by integrating the learning outcome at the beginning and throughout an experience and again, when you reflect on the child’s learning and development over time. This is about flipping your thinking and being playful.

In another example, in this short video, Dr Anne Meade and Lucy Hayes from Daisies can be seen talking about how they plan using the red section of Te Whāriki and how tamariki actually enjoy being part of this.

Together tamariki, parents, whānau, and kaiako develop a shared language for describing the learning outcomes in relation to what matters to them. For example, undertaking a four-hour tramp to the top of Tarikākā, tamariki were using words like “resilience” as they prepared for the walk and talked about their learning.

How Anne and Lucy use the learning outcomes aligns perfectly with what Claire talks about – organising or designing curriculum to guide teaching and assessment.

So goals and learning outcomes are a key element of designing curriculum; they guide and inform pedagogy and offer possibilities for shifting the way we think about planning and assessing children’s learning. Learning outcomes should be part of the conversation from the start, in the middle, and again at the end of a cycle where the process begins again.

Learning outcomes have the potential to shift the focus from what kaiako know, to what kaiako, tamariki (together with family, whānau, and community) know, do, and imagine together.

This brings us to the end of this webinar.

Unuhia te pō, te pō whiri mārama

Tomokia te ao, te ao whatu tāngata

Tātai ki runga, tātai ki raro, tātai aho rau

Haumi e, hui e, tāiki e!

From confusion comes understanding

From understanding comes unity

We are interwoven, we are interconnected

Together as one!

Mā te wā.

-

Resources from webinar 2

Download a PDF version of Webinar 2 slides:

Webinar 2: Unpacking the goals and learning outcomes (1.6MB)

Anne and Lucy: Learning outcomes contributing to curriculum design video

-

Transcript

Webinar 3: Strengthening bicultural practices

Kia ora and welcome to the third webinar of a series made for a Ministry of Education professional development and learning programme to support the implementation of Te Whāriki (2017).

Let’s start with karakia.

Tūtawa mai i runga,

Tūtawa mai i raro,

Tūtawa mai i roto,

Tūtawa mai i waho,

Kia tau ai te mauri tū, te mauri ora ki te katoa,

Haumi e, hui e, tāiki e.

I summon from above,

I summon from below,

I summon from within and the surrounding environment

The universal vitality and energy to infuse and enrich all present

Unified, connected, and blessed.

Webinar one of this series, developing local curriculum, focuses on exploring what matters here. Webinar two, unpacking the goals and learning outcomes, provides some opportunities to deepen understanding about the why, what, and how of these in relation to your contexts. Webinar three, this webinar, is about strengthening bicultural practices. While each webinar can stand alone, the intention is that, together, they represent an holistic view of curriculum design using Te Whāriki (2017).

In this webinar, we look at why a bicultural curriculum is important, and to whom. We do this by re-visiting of Te Tiriti o Waitangi / Treaty of Waitangi. How does knowing about this support us to work together as partners with a shared interest in the wellbeing of all tamariki?

Next, we look at Te Whāriki, which offers us a framework as a basis for both understanding and action.

After that, we have some ideas to share before we end with some words of wisdom from two kaiako, Jacinta and Marlena, who work at Karanga Mai, a teen parent unit in Christchurch. Their centre has been on a journey, a long road trip full of adventures, to embed a philosophical commitment to being bicultural.

We end where we began this puzzle, by asking you how you will continue to challenge yourselves as kaiako.

Being bicultural means having a strong sense of your own cultural identity and awareness of how your beliefs and assumptions are culturally located. As highlighted by writers such as Mason Durie, this applies regardless of whether you are Māori or Pākehā. Without an awareness of cultural self, kaiako are unlikely to achieve the intentions and aspirations expressed in Te Whāriki and its commitment to biculturalism. Being bicultural means accepting that sometimes your views may be challenged. You don’t have to have the answers right there and then. However, it’s important that you're curious and committed to ongoing learning.

Let’s start with the origins of Te Whāriki. We have the metaphor of a whāriki for our curriculum courtesy of Te Kōhanga Reo Trust.

As Lady Tilly Reedy said in her kōrero celebrating 20 years of Te Whāriki in 2016, “We wrote Te Whāriki in te reo Māori. We sought the understanding and beliefs of our matua, of that wealth and knowledge that belongs to this land. It was an opportunity to signal to Aotearoa, and eventually to the rest of the world, that we as Māori exist in New Zealand and that we have much to contribute.”

“Te Whāriki for us … is centred on the mokopuna; Te Whāriki talks about empowering the mokopuna to learn: ko te whakamana o te mokopuna ki te ako ... So when you step into early childhood services, central to the learning in there is the mokopuna – that concept is very important to Māori. Kia kaha koutou kia tautoko te mokopuna.”

Lady Reedy goes on to say the aho (the strands of Te Whāriki) are about mana mokopuna and the role of kaiako is to protect these. You can hear how Lady Reedy explains these in the short clip. You’ll hear how she conceptualises mana mokopuna as applying to all mokopuna. The aspirational framework of Te Whāriki is inclusive of all cultures, languages, and customs yet it emerged from te ao Maōri.

Another one of the original writers of Te Whāriki, Professor Helen May, tells the story about how the Māori Working Group for designing the original curriculum came back first of all the working groups with the metaphor of a whāriki based around the agency – the mana – of the child.

Again, Lady Reedy talks about Te Whāriki being for “mokopuna from every walk of life, from every nationality, from every indigenous people – centre it on the mokopuna”.

This is an important whakataukī where the centrality of mokopuna to whakapapa is foundational to whānau. Mokopuna is really two words – moko, refers to the blueprint from tīpuna and puna means a well spring of life. This whakataukī translates as “Stand strong, o moko. The reflection of your parents. The blueprint of your ancestors.

The whakataukī introduces the principles of Te Whāriki and celebrates the mana of the child – the child’s potential – as building on the past and looking to the future. This concept is proudly Māori and encapsulates why being bicultural is important. Not only do we have an obligation; we have a responsibility. Listening to how Te Whāriki was developed as a framework with the child at the centre, it is really clear why it matters to children. A recent report focusing on what matters to mokopuna Māori released by the Children’s Commissioner shared some insights from children and young people about their identity.

This young person summed it up as whanaungatanga and you can read in the quote how important relationships and whakapapa are. Understanding how to support these are good reasons to strengthen bicultural practices and it has to start with Te Tiriti / The Treaty. How do we make Te Tiriti / The Treaty real in our services? What are our obligations? How do these translate into everyday practice for kaiako? What do we need to do to move beyond a token gesture?

One of the first places to begin is our history. We can think about our founding document as the basis for sharing power between two nation states: The Crown, or tangata tiriti, and ngā iwi Māori, tangata whenua. Tangata tiriti includes all non-Maori and is a term coined by Sir Eddie Durie. This is reiterated in Te Whāriki on page three where it says “Te Tiriti / The Treaty is seen to be inclusive of all immigrants”.

However, there is more than one version of Te Tiriti: Several drafted in te reo Māori (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) and one drafted in English (Treaty of Waitangi). Take a look at the table: The words in bold highlight the most contentious differences between versions for two of the three Te Tiriti / The Treaty articles. For example, for Māori, the Articles of Te Tiriti guaranteed tino rangatiratanga – sovereignty; rights over taonga – tangible and intangible, and the same citizenship rights as the new settlers.

For the Crown, tino rangatiratanga was interpreted as Maōri ceding their sovereignty rights to the Crown. Rights over taonga were limited to ownership over property but, and it is a big but, property rights and the concept of kaitiakitanga/collective responsibility for tribal land ownership was dismissed; neither were the intangible taonga, like te reo Māori, considered.

In 1986, the Waitangi Tribunal ruled that Crown Law and the versions of Te Tiriti were at odds and needed to be rectified. It also ruled that te reo Māori was a taonga. That te reo Māori required legal protection because it was under threat and the Ministry of Education should resource all children who wanted to learn te reo, to be able to do so.

Resources:

Sir Eddie Durie Wai 11 Report, 1986

Treaty resource centre- free resources and training

Ministry of Culture and Heritage resources

Jennie Ritchie is one scholar who has consistently raised concerns “that the non-prescriptive nature of the document allowed teachers to ‘do Te Whāriki’ without addressing bicultural aspirations”. Ritchie, J. (2018). A fantastical journey. Reimagining Te Whāriki. Early Childhood Folio, 22(1), 9-14.

The Education Review Office’s 2013 report Working with Te Whāriki noted, that despite many services including Te Tiriti o Waitangi in their philosophy statements “often bicultural practice meant the use of basic te reo, some waiata in the programme, resources such as puzzles that depicted aspects of te ao Māori, and posters and photographs that reflected aspects of Māori culture” (Education Review Office, 2013, Working with Te Whāriki, p. 13).

Jenny Ritchie comments “moving beyond such tokenism remains a challenge for many teachers and programmes”. Ritchie, J. (2018). A fantastical journey. Reimagining Te Whāriki. Early Childhood Folio, 22(1), 9-14, p. 10. Now let’s look to Te Whāriki for some guidance.

We explored this image in the first webinar. Among other things it represents the bicultural framework of the document. Just like Te Tiriti / The Treaty – there are two documents that make up Te Whāriki and they are not direct translations. If you haven’t already had a look at Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo, make a point of doing so soon. You'll notice that the whakataukī introducing the strands are different. Different concepts in one document; the same aspirations for all mokopuna but expressed differently.

Te Whāriki includes a lot of information for kaiako to use to strengthen bicultural practices. Every strand has an English statement explaining the strand as well as a Māori interpretation. Each section and every strand uses a whakataukī to illuminate and reveal te ao Māori thinking.

As a way to support kaiako to use the whakataukī, a set of cards was developed for the sector. On the back of each one are provocations to think about. You may like to consider; how do you give children rangatiratanga (agency, voice, choice) in what they learn? And remember, this applies to all children but for children who whakapapa as Māori, understanding who they are and where they are from makes a difference.

Not all the whakataukī are produced as cards. As a strategy to engage with whānau, mana whenua, and kaupapa Māori approaches, you could develop questions for your own whakataukī cards. That means finding out what whakataukī are used in your rohe. What is the context of their origin? How are they relevant to your mahi?

The responsibilities of kaiako cards offer a great resource when it comes to clarifying what is a rich, complex role. They celebrate roles as kaiako at every level in early education. If used to prod and prompt thinking, we begin to consider education as drawing out the thinking, the ways of knowing, and the sense-making processes, that support us to live successfully as contributing citizens in a bicultural Aotearoa.

Card five captures the intention of cultural competence: It's really clear – for those of us who are not fluent in te reo, we need to take steps to increase our fluency. If we are unfamiliar with tikanga, we need to find ways to learn. It is not so much a strategy as a directive. Now take a look at this learning outcome for the Contribution Strand: Te rangatiratanga – recognising children’s mana as learners. As you think about this, reflect on the different interpretations of Te Tiriti / The Treaty.

Making it happen however, is up to you – the learning outcome cards, the whakataukī cards, and the responsibilities of kaiako cards give us some building blocks. Everyone of us has bicultural obligations stemming from Te Tiriti / The Treaty. Kaiako are all leaders – pedagogical leaders, leading learning in services.

To be a leader strengthening bicultural practices is a challenge that takes courage and commitment. It also means being familiar with relevant resources and strategies.

In Webinar one, “Where do we start? Designing local curriculum”, we looked at some of the guiding documents and noted that there are obligations to be culturally responsive in Tātaiako and Tapasā as well as the newly developed Our Code, Our Standards. These all make it clear that kaiako have responsibilities to be knowledgeable, ethical, respectful, and equitable. But we need leadership to bring them to life so they don’t languish on shelves.

Another guidance document is Te Whatu Pōkeka which uses a Kaupapa Māori approach to assessment. Assessment practices have to be consistent with the principles of Te Whāriki and with Te Whatu Pōkeka in Māori immersion services and for mokopuna Māori in mainstream services too.

When used in conjunction with the responsibilities of kaiako section of Te Whāriki, and the building blocks for curriculum design like the responsibilities of kaiako cards, you can see numerous opportunities to puzzle about practices. Take the statement on this slide for example, assessment involves making visible learning that is valued within te ao Māori.

Think about the ways you make this happen.

And now to the final part of this webinar.

In a short snippet from a video about strengthening bicultural practices, Jacinta, and Marlena, from Karanga Mai, talk about the numerous ways they strengthened their relationships with mana whenua. They worked to do this on several fronts. Marlena became involved in kapa haka at school and visited the marae. Jacinta facilitated a Tātaiako workshop for the team.

Take a moment to read through the points on this slide. Be proactive, be courageous, and be connected. Jacinta and Marlena talk about the importance of facing the challenge by taking the initiative, working collectively, and making sure that your shared vision is communicated. Their message is clear on reciprocity: Rather than asking others all the time, think about the personal research you bring to the kaupapa. What professional dispositions are associated with these strategies?

One important point to remember is that leadership – the obligation and the responsibility to be bicultural – “lies with all of us”. In this quote, Jacinta takes us back to that original vision of the mana of the child and the reason why we need to stand up as leaders. She reminds us that what we, as kaiako, can influence is the environment children experience. And Marlena added that the starting point to strengthen bicultural practices is very simple – “just open the door”.

In this webinar series we addressed the three key areas: designing local curriculum, unpacking the goals and learning outcomes, and strengthening bicultural practices. We introduced some new ideas like the puzzle of practice and design thinking to support your calls to action.

When Dame Whina was addressing rangatahi about Te Matakite o Aotearoa - the Māori Land March, she said “You have to show you are prepared to take up that cause”. Taking on board her call to action – how will you challenge yourself, your colleagues, and your whānau? These are ngā wero, the challenges, in front of us.

In Matika, maranga, we wanted to create a sense of real purpose – digging hard, digging deep, and even breaking the kō, the digging stick. Kia kaha, be strong.

Now it’s time to close the webinar with our karakia mutunga. We want to thank you for joining us on Matika, maranga and we wish you well looking for new puzzles of practices as you seek new horizons.

Ka whakairia te tapu

Ka wātea ai te ara

Kia turuki whakataha ai

Kia turuki whakataha ai

Hui e, tāiki e.

Restriction are moved aside

So the pathway is clear

To return to everyday activities

To return to everyday activities.

Mā te wā.

-

Resources from webinar 3

Download a PDF version of Webinar 3 slides:

Webinar 3: Strengthening bicultural practices (1.3MB)

Lady Tilly Reedy on 20 years of Te Whāriki

“Just open the door” - words of wisdom to support bicultural practice

Tiriti o Waitangi / Treaty of Waitangi resources

- Report of The Waitangi Tribunal on The Te Reo Maori Claim - Sir Eddie Durie Wai 11 Report, 1986

- Treaty Resource Centre – free resources and training.

- Te Manatū Taonga Ministry of Culture and Heritage resources