Te aratohu waihanga marau ā-rohe

Local curriculum design guide

Te Whāriki provides a framework for curriculum in early learning services. Each service designs a culturally responsive and local curriculum based on learning priorities and aspirations for tamariki and whānau in their setting.

The curriculum design diagram supports curriculum intentional decision making for each early learning service.

Curriculum decisions are made in the moment or through short, medium, and long term planning.

The diagram below shows a process that will help you to review and design your local curriculum based on decisions about what matters here. The process is circular but you may need to go back to previous steps sometimes to revisit your decisions.

Select the grey circles to learn more about each step.

On a mobile the diagram is best viewed in landscape. You can also read the explanations in each of the step sections below the diagram.

-

Explanation of the diagram

Curriculum design diagram

The diagram depicts a whāriki to symbolise the way in which each stage in the process of curriculum design is built on a foundation of Te Whāriki.

The process needs all the pieces or steps shown to fit together to form the overall whāriki.

The speech bubbles used for the process demonstrate that curriculum design is collaborative. It involves building learning partnerships and talking together.

The colours of the speech bubbles reflect the role of the principles, strands, pathways to school, and responsibilities of kaiako in Te Whāriki in designing your curriculum.

Download the guide

- Local curriculum design guide – English guide (553 KB PDF)

- ‘Akapapaʻanga kaveinga ‘āpiʻi i roto i te ‘ōire – Te Reo Māori Kūki ʻAirani guide (752KB PDF)

- Tūhulu ki he fokotu’utu’u silapa faka’apiakó – Lea Faka-Tonga guide (752KB PDF)

- Taki mō te fatuga o he takiala fakalotoifale o nā matākupu akoako – Te Gagana Tokelau guide (752KB PDF)

- Ta’iala e fua ‘i ai matā’upu a’oa’oina i le lotoifale – Gagana Sāmoa guide (752KB PDF)

- Tau hātakiaga ma e tau tālagaaga he tau fakaholoaga fakaako – Vagahau Niue guide (752KB PDF)

Curriculum design steps and examples at each step

-

Get to know our people and place

How to get to know your people and place

This is an opportunity for us to reflect on what we already know and what we need to find out about our tamariki. Fostering learning-focused relationships with parents and whānau plays an important part in helping us find out about our tamariki.

For example we look at:

- the identity, language, and culture of our community

- the knowledge, perspectives, and tikanga of mana whenua

- what tamariki know and can do

- the interests and aspirations of our tamariki, whānau, and kaiako

- what support our tamariki need as they transition to school/kura.

Start where your feet are

In this video Professor Wally Penetito shares his thoughts on where to start with curriculum design. He says:

- start where your feet are

- connect to the people who belong.

-

Decide on learning priorities

How to decide on learning priorities

We think about:

- What matters here?

- What learning are we prioritising?

We make decisions based on:

- what we have learnt about our people and place

- the goals and learning outcomes in Te Whāriki

- our centre’s philosophy and priorities

- rich opportunities for learning.

Learning outcomes contributing to curriculum design

In this video, Anne Meade and Lucy Hayes from Daisies Education and Care Centre discuss how they use the learning outcomes in curriculum design.

-

Plan our response

How to plan our response

Responses can be planned or spontaneous. There can be layers involved in planning our response.

For example we look at:

- responsibilities of kaiako, underpinning theories and approaches, teaching practices and strategies

- the ways in which we are working towards our priorities

- making intentional decisions around people, materials, time, and space, examples include, how we create our rosters (people), what resources we need (materials), how we organise the day (time) and how we best utilise our spaces (space)

- interacting intentionally and thoughtfully with tamariki

- what professional learning kaiako are engaged in.

Planning conversations: The key to promoting scientific thinking

A kaiako inquiry at a Montessori centre showed that while children had access to well-stocked shelves of Montessori materials for science, they could do more to foster children’s scientific thinking and dispositions. Questions prompted by their reading of the Exploration | Mana aotūroa strand in Te Whāriki were:

- Do we extend understanding following on from presenting materials?

- Do we recognise science happening in other areas of our centre?

- Do we foster exploring, asking questions, observing, testing ideas, making representations, and sharing findings?

The team engaged a facilitator specialising in science who recommended Marilyn Fleer’s research. This highlighted that conversations with children are the key to building scientific thinking. This shifted the focus towards the nature of their conversations in their planning. For example, they looked at ways to model a sense of wonder through specific questions such as, “What would happen if … ?”. They also focused on planning scientific processes such as data recording and sharing findings. By discussing and deciding on these strategies ahead of time, kaiako addressed their inquiry questions with confidence and consistency.

Read more of this story in the stories of practice on the Deciding what matters here page.

Planning communication strategies

Three-year-old Poppy attends a Hastings kindergarten and uses a combination of signs, actions, and vocal sounds to communicate. With the support of her parents and a speech-language therapist, kaiako and children are learning about how Poppy sends messages, such as wanting to play or needing some help. The kaiako team plan the following ways to reduce Poppy’s frustrations and improve their communication with her:

- observing her to get to know her unique communication strategies

- being patient and giving her time to get her messages across

- supporting her communication with others, by encouraging those who know her well to provide a voice for her when that is helpful

- giving her encouragement and feedback when she seeks attention from others in positive ways

- modelling for her ways of getting attention from kaiako and children, such as touching them on the arm, smiling, or pointing to something

- using visual communication aids, including pictures and home-made photo books.

(Adapted from He Māpuna te Tamaiti: Supporting Social and Emotional Competence in Early Learning, p.17)

One community whānau

ECS and school kaiako in the Learning journeys from early childhood into school Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) project met regularly to discuss transition to school in their community. Observations in each others’ settings provided the chance to discuss practice and develop mutual understandings based on Te Whāriki and The New Zealand Curriculum.

Joint curriculum planning, for example, around themes such as Matariki or the Olympics, allowed expertise to be shared.

ECS kaiako and new entrant teachers developed a range of action research mini projects to work on together.

Some examples include:

- planning ways to support friendships that could be continued at school

- planning strategies and resources that would help children understand the rituals, norms, and rules of the school playground such as shared books to discuss this, safe and interesting play spaces, and strategies to help children initiate play with others.

Reference: Peters, S., Paki, V. & Davis, K. (2015). Learning journeys from early childhood into school. Teaching and Learning Research Initiative.

This is one of the stories of practice on the Pathways and transitions page that explores supporting tamariki to navigate transitions.

-

Make it happen

How to make it happen

Here is where we put our thinking and planning into action.

As we take action we may revisit steps in the curriculum design process.

Learning happens in diverse ways.

Homebased kaiako planning in action

Key points

- Domestic tasks are contexts for learning

- Playful interactions refine working theories

Listen to this example of a homebased kaiako planning in action. They see an opportunity in an everyday event to help tamariki refine their working theories about the usefulness of pegs.

-

Transcript

It was one of those hot, muggy, sunny days that you get in Auckland sometimes and I went to visit an educator with three children and a baby. So we sat outside under a tree on a blanket and looked at her pegging out the washing, which seemed to include hundreds of her husband’s work socks. One of the children noticed that the pegs were a different colour and was talking about it and wondering why that was. He asked the educator and she said, “I don’t know. Why do you think the pegs are a different colour?”

The children started talking amongst themselves and came up with some ideas. One child said that his father reckoned that red sports cars went faster than any other colour so perhaps the red ones were very fast pegs. After some talking around why pegs were different colours, what the colours were, and how pegs worked, the children came up with the idea that maybe the pegs were different coloured because some pegs were stronger than others. And that the black pegs would be the strongest of all. So I asked them how would they prove that? The children decided that they would have to do some tests to check which pegs were the strongest. When I asked what sort of things they could test for the pegs, they said well if they hung things on the line with pegs, the one peg that hung the heaviest thing (whatever that was) was the strongest peg.

So I said, "Okay but how are you going to make sure that you do this fairly?" They decided they could put things in the socks as there were plenty of socks. The more stuff they put in, the heavier the sock would be and so the stronger peg would be that held it up. They decided the best thing they could do was marbles. So I said, “How do we make sure it is fair with the marbles?”

We got into a big discussion about how they would measure the marbles. Some children thought they could measure them with weight on scales. Some children thought they could line them up one by one and the same number of marbles would weigh the same. Other children said well we could count them and that would be quicker. So over the next couple of weeks they did all sorts of things with the marbles and the socks to see which was the strongest. Eventually they came up with the finding, I think we would say, that all pegs are equally strong. I was a bit disappointed that nobody gave me a red sports car to try out the father’s theory but there you go.

This story is an example included in the Home-based early childhood education downloadable workshop on rich learning opportunities.

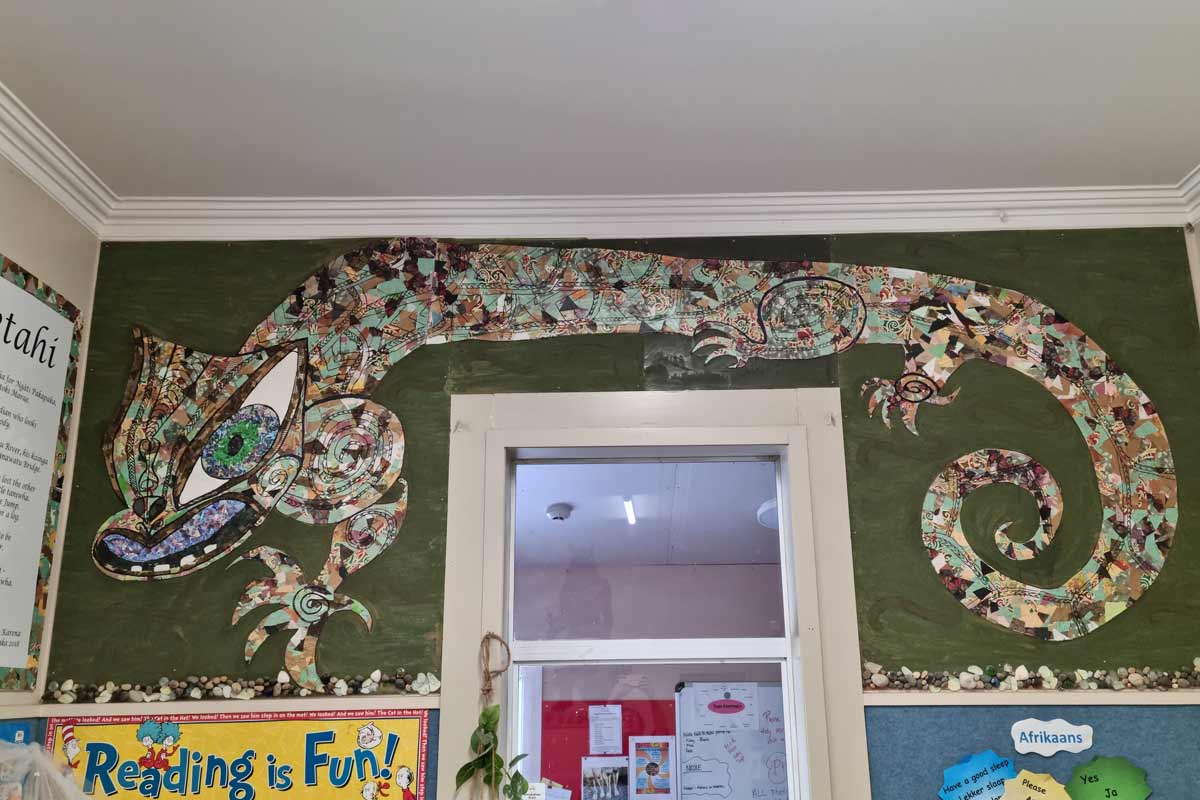

Local history a feature of curriculum

Kaiako at this kindergarten have made local history and pakiwaitara a feature of their curriculum. Watch the different ways children’s learning is being extended because of the ongoing focus they have chosen.

This video is part of the Mathematics page that discusses how Te Whāriki positions mathematics as one of many forms of expression that tamariki need in order to communicate successfully and widely.

-

Transcript

Jasmine Heads: Bluff is a small fishing community. The kindergarten is situated in the middle of our community in close proximity to both schools. Seventy-five percent of our whānau are Māori that attend our service.

At the beginning of this project I was not confident with mathematics. I purely thought of mathematics as being number. So I didn't really see where we fitted into the picture of things. One of the biggest outcomes for the team was to raise the awareness of mathematics and mathematical concepts within their environment at home, within the community – producing a resource that was available to families that was free and that they could utilise that was easy.

We wanted whānau to recognise the mathematical concepts within everyday experiences with their children – whether it be at home, in the supermarket, going to their local marae. Looking at all the different shapes, patterns, and number because number is important but it's not the only mathematical concept that they can see.

We created an adventure pack for the children to take away from the kindergarten. We designed the pack with mathematics in mind of course. Every activity has a mathematical concept behind it. One of the main concepts was our community I spy which was a collection of photo cards that we took of different landmarks/aspects around our community where children were asked to find them. Behind each photo there is a question to ask like where the photo is located. So we asked the children to tell us where they located the picture. We also asked the children a question it could be; was there pattern around this area, was there shape, was there number? All different mathematical concepts to look for. We also found that with our activity pack it crossed over into literacy. So we have also provided an assortment of books that go with the pack as well.

The other thing that we also added to the pack was information about the community. Walks that are made available for our families, free activities around our community that a lot of whānau didn’t actually even know about. Historical aspects to our community that children could also look at that were outside of the actual activity itself. That was information which we want to build on.

The other thing that we added to it was a guide to their hīkoi or driving. We produced two packs. One was a driving pack for whānau that had access to a car and then we also had another two packs that were made available to whānau that didn't have access to a car but either families could try them. Then we also added a scrapbook which is the tamariki documenting their journey. We called it Tamariki Kōrero which is the child's voice and it was a way for them to revisit as well.

Also within the packs we have provided the whānau with cameras to video or take photos of their journey. This has been really popular as the children have been allowed to take over and do all the filming and things themselves. So it's really nice when the backpacks come back to the office that we can actually look through that footage and we have a bit of a laugh and it's lovely.

We want to have a whānau evening at the end of this project. We thought that maybe we would put it into a wee movie for families to see like with captions of all the families' journeys all put together in a wee movie. We thought that would be kind of nice and to give it to the families that participated.

I think a lot of the time like our parents thought it was going to be number. A lot of them knew shape and colour come into it but locating, distance, all the measurements, and just lots of different things that they've used in the everyday experiences but they didn't realise that there was a mathematical education for their children behind it.

One of the best parts of the feedback was hearing from family and whānau that they had fun and that they were spending quality time with their tamariki. Mathematics was fun. It wasn't actually all hard work.

Helen Jackson: Our vision was that we wanted whānau to participate, have fun doing it, and just have a great time with their tamariki. The outcomes we wanted was to have whānau feeling confident that they could be teachers at home or away or at kindergarten. But just that they had confidence about maths and that they were able to bring something with their children as well.

To get our whānau and community involved we started off having an activity night where we invited whānau to come at night with their tamariki and we had a PowerPoint presentation. It was just a wee short thing about our objectives of what we were doing so they could come on board with what we were doing and support us, as well as us supporting them. Then the next thing we did is we got them to move around the kindergarten to different station points and work with their children doing mathematical things that they would actually find at home. We tried to use resources that they had at home so they could take what they learnt that night and take it back home and maybe have a go with it at home. That it doesn't have to cost them money. I think some of our whānau were thinking I have to buy them maths books to take our children to a different level. They don't need to do that now. They can see that they can do it themselves which is really exciting for us.

Some the feedback that we got from the activity night was that it was interactive – that they could participate. Whānau before thought that it was written format as maths but actually being involved and being interactive with their children was a better way to teach their children mathematics.

One of the most exciting things about these adventure packs is that whānau are coming to us and having huge kōrero with us about what's the next thing, which is really exciting for us because we didn't even know if they would take this concept on at all. But they are asking what's the next bag going to be? What else can we do? So it's really exciting that they came on our journey with us and actually now they are wanting to lead it a bit more.

Perry Savage: It was great to see with the kids and that then all the different aspects of maths. Stuff that you never knew that was like that – especially with fishing and all the different mathematics we use for navigation and stuff. Then go down the street and there's mathematics everywhere. One of the biggest things is maths is more than just numbers for the kids.

Roxanne Frahm: From the maths backpacks my family learnt that maths is really happening out in the world, in the real world that we live in – here in Bluff. That being able to see what numbers are different, and see shapes and count how many there are was actually useful and relevant. It was really exciting and great fun.

The maths backpacks are really constructive. I was just blown away by what a cool experience it was for my son to go out there and use his maths skills and see that they were useful. When we buy petrol reading numbers was actually a really useful thing to be able to do. Because those numbers told us how much the petrol cost. It was a useful thing that he could tell that it was a nine. He was really proud of himself.

The other thing we really loved about the maths backpack was taking Grandad around Bluff and introducing him to lots of local landmarks. It gave us an activity to do with a visiting family member and that was really exciting. I was just like we need more of these. I want to do this in the future.

-

Find out what and how tamariki are learning

How to find out what and how tamariki are learning

- Observe and reflect.

- Talk together and record.

- Consider what learning is happening for tamariki and what to do next.

- Discuss with parents and whānau.

Assessment in Te Whāriki says "only a small amount of assessment will be documented. Formative assessment happens on the go as you teach, as well as in a more formal and planned way."

For more see the Assessment downloadable workshop, particularly slides 4–8.

Expectations of assessment in Te Whāriki

In this video Professor Claire McLachlan outlines the new expectations of assessment in Te Whāriki (2017).

-

Review and respond

How to review and respond

This involves reflecting, reviewing, and evaluating on the experiences and the process.

Consider:

- the impact of the experience on learning

- how effectively we responded to our people and place

- what we would do differently next time

- what we will take forward to our next curriculum design cycle.

The use of video coaching to evaluate kaiako interactions

In an early learning service, a kaiako used video coaching to evaluate the impact of his interactions on children’s motivation to respond. This showed that a high proportion of his interactions were questions. Often the questioning drew little or no response from tamariki and didn't encourage tamariki to talk to each other.

Alternative strategies suggested during the coaching sessions included:

- using commenting alongside tamariki

- extending wait time for responses

- using sentence starters such as; “I heard you say ... ”; “When I was ... ”; ”I am thinking about ... "

- encouraging children to speak to each other.

Trying these strategies out, his interactions were more conversational. There was more turn taking with tamariki sharing their thoughts and ideas in response to his. Interactions felt easier and more natural. Asking fewer questions, making more comments, and consciously allowing time for tamariki to respond is a work in progress. Video coaching sessions continue to be used to help evaluation.

This story of practice is also found as part of the Talking together, Te kōrerorero resource in the Conversations and questions section.

Strengthening infant and toddler practice

Observations at an infant and toddler centre formed part of an evaluation into kaiako practice with infants and toddlers. Kaiako found that interactions were inconsistent and often rushed, with minimal conversation. As well, they found that rigid routines and older children were sometimes interrupting the play of infants and toddlers.

The team explored Te Whāriki to investigate how they could guide practice and improve learning outcomes for children. In particular, kaiako aimed to build their understanding of how to provide a physical and emotional environment that supported infants and toddlers to learn and develop.

This investigation highlighted the need for kaiako to:

- allow more time and space to strengthen relationships between kaiako and infants and toddlers

- provide a calm and positive learning environment

- provide safe places for infants and toddlers to explore

- ensure flexible and unhurried daily routines

- strengthen communication between kaiako and whānau.

An improvement plan to address these points was put into place. The centre trialled a number of strategies and are working to refine these. Kaiako are now consulting with an ECE environment expert to identify ways to support the provision of a safe, yet challenging learning environment for infants and toddlers.

More information about this story of practice is found as part of the Stories of practice from kaiako and leaders, a focus on learning that matters here section.

Evaluation of transition to school

Whānau at a playcentre evaluated how well relationships within the playcentre, and with the local schools, were supporting tamariki in their transition to school.

They were surprised to find that:

- in most cases whānau were leading the transition process with little input or support from playcentre members

- some whānau did not see it as the role of playcentre to support transition to school.

One of several responses to their findings was the creation of a folder with information and enrolment forms for all contributing schools. The development of this folder led to interesting conversations with children. Space was provided in the folder for children’s questions, valuing the child’s voice in the transition process.

Children identified that they would like photographs of the school, past playcentre graduates, and school uniforms to be included in the folder. Gathering this information has strengthened relationships with schools. New entrant teachers now share information about schools’ transition programmes and arrange to visit the playcentre to speak with whānau.

More information about this story of practice is found as part of the Stories of practice from kaiako and leaders, personalised pathways to school and kura section.

Supporting bilingual oral language development

At a mixed aged, Māori-focused, bilingual centre, oral language is an important component of curriculum planning. Being a confident and strong speaker is a gift in te ao Māori, therefore kaiako chose to focus their internal evaluation on how well they support tamariki acquisition of oral language.

Data collected to inform this inquiry included analysis of:

- the learning stories written over the past six months

- event recordings of sustained conversations with each child

- how often tamariki experienced waiata, stories, and listening activities during one week.

Analysis of this data revealed three areas that required work:

- making language support visible in learning stories

- having quality conversations with two-year-old boys, because practice with this cohort of tamariki was not as strong as with other groups

- finding more opportunities to read books to all tamariki.

Staff identified a range of actions to improve practice in these areas, including:

- creating specific language learning goals for two-year-old boys

- focusing on language in learning stories

- using direct quotes from children in assessment documentation to illustrate progress over time

- planning more opportunities to read books throughout the day

- making a concerted effort to speak te reo Māori during set hours each day.

More information about this story of practice is found as part of the Stories of practice from kaiako and leaders, affirmation of identity, language, and culture section.

For useful information on supporting bilingual and multilingual language development see Supporting bilingual and multilingual learning pathways in the Talking together, Te kōrerorero resource.

Observe, reflect, share

Key points

- Personalising responses to belonging and wellbeing

- Kaiako collaborating to solve an issue

Kaiako were concerned for a child who was very reluctant to come to a shared kai table at lunch time. A chat with the boy’s parents revealed that eating sufficiently at home and at the centre was an important learning priority for them.

One day a kaiako noticed that this child came to the table before the other children and he ate really well. She said to colleagues, “I think his reluctance has got something to do with him liking to come to a clear, clean table”. Another kaiako in the room then tested this hunch the following day. Noticing that the boy was not at all keen on coming inside for karakia kai she sat alongside him and said, “Would you like to come and have kai now? If you wash your hands then you can be first at the kai table while everyone else is at their hui.” The child nodded and went straight off to wash his hands then had his kai.

Seeing these adjustments to the normal routine working, all kaiako used the same personalised response while the child grew accustomed to eating with others.

In this centre the leader actively encourages "observe, reflect, share”. Much of their formative assessment of tamariki happens in action. Kaiako are encouraged to treat their observations as hunches rather than absolutes and to share these with other kaiako.