Te tuakiritanga, te reo me te ahurea

Identity, language, and culture

Tōku toa, he toa rangatira.

My bravery is inherited from the chiefs who were my forebears.

Key ideas

Te Whāriki affirms the identities, languages, and cultures of all children, whānau, kaiako, and communities from a strong bicultural foundation.

- Each ECS setting’s curriculum whāriki recognises the place of Māori as tangata whenua of this land.

- All children are given the opportunity to develop knowledge and understanding of the cultural heritages of the partners to Te Tiriti o Waitangi | Treaty of Waitangi.

- The integration of kaupapa Māori concepts (Māori values and philosophy) and te reo Māori (Māori language) supports cultural, linguistic, social, and environmental diversity.

There are an increasing number of migrants in New Zealand, and, as in any country with a multicultural heritage, there is a diversity of beliefs about childrearing practices, kinship roles, obligations, codes of behaviour, and the kinds of knowledge that are valuable.

- From a bicultural foundation, the early childhood curriculum affirms and celebrates cultural differences, and aims to help children gain a positive awareness of their own and other cultures.

- It enables all peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand to weave their perspectives, values, cultures, and languages into the early learning setting.

-

Stories of practice

Stories:

- Tūrangawaewae: giving children a place to stand at Te Rourou Whakatipuranga O Awarua

- The joy of finding parallels – Steiner philosophy and te ao Māori

- A curriculum embedded in iwi values, stories, and reo

- Partnering with Māori children, parents, and whānau

- Songs from the heart – embedding Tapasā

- Supporting former refugee families

- Promoting identity, language, and culture in a Montessori curriculum

- Monolingual teachers in multilingual centres

- Reflecting a multicultural community

- Museums as a resource for learning

Tūrangawaewae: giving children a place to stand at Te Rourou Whakatipuranga O Awarua

Key points

- Local hikoi as a way of learning and connecting

- The marae as a place of learning

The kaiako and whānau at Te Rourou Whakatipuranga O Awarua discuss the uniqueness of their community and reflect on the ways the early childhood setting’s connectedness to the community supports children’s identity, language, and culture.

The joy of finding parallels – Steiner philosophy and te ao Māori

Key points

- Researching local stories

- Deepening te ao Māori

A way to deepen understanding of Te Whāriki is to explore the synergies between the curriculum and a service’s existing purpose or philosophy. For example, Māori and Steiner world views each propose a unique understanding of the world specific to their culture. There are however some clear similarities between them. Both world views have a profound respect for what the child brings, who the child is – the mana of the child. Both also have a strong oral storytelling tradition.

At Christchurch Rudolf Steiner Kindergarten, kaiako are undertaking an internal evaluation of their commitment to honouring the bicultural nature of the curriculum. This evaluation has highlighted to kaiako that they could enhance their practice further. As part of this process, kaiako have drawn on kaupapa Māori theory in Te Whāriki as a starting point for increasing their knowledge and reviewing ways to strengthen this aspect of their curriculum.

Kaiako know that their regular use of well-known stories and legends that they have told and recreated over the years have promoted te reo Māori and aspects of tikanga learning well. However, through the following the process of internal evaluation, kaiako became aware of ways they could be extending this rich oral storytelling tradition by adding more local, place-based stories to their repertoire. They have gained knowledge of these through attendance at Early Years Community Cluster meetings, and by using the Ngāi Tahu Atlas, a resource of place names, history, and stories.

This has led to them prioritising the following actions:

- investigating the story behind how the school came to be named “Te Ara Korowai” – cloak around the school – who gave this name and why

- telling a story of how the creatures of the awa lived during walks with tamariki

- creating stories in the Steiner tradition, for example, felt puppets and mats that are built around the people and creatures who once lived in the local area

- adding these local stories to tamariki “Journey Books” which travel between home and centre, so parents/whānau benefit and contribute as well.

When it comes to evaluating the impact of their actions, kaiako will look for:

- more reenactment of local stories through the drawings and artwork initiated by children

- references to local stories in children’s everyday conversations

- whānau enthusiasm about the focus on local curriculum.

Representing and respecting elements of both kaupapa Māori and Steiner fairytale is bringing challenge joy, satisfaction, and learning for kaiako.

A curriculum embedded in iwi values, stories, and reo

Key points

- Localised curriculum development

- Three centres: shared endeavours

The Maniapoto Trust Board has developed its own curriculum around their eight pou (posts), each of which represents an ancestor important to their iwi. Each pou depicts an expertise and skill that is woven into each of their centre’s curriculum. They are also guided by five key curriculum components: whānau ora, whanaungatanga, taonga tuku iho, te taiao, and he anga whakamua.

Everything is done from a Maniapoto base, weaving a curriculum specific to their area. They use the stories, waiata, and language from Maniapoto to drive learning.

All three centres under the Trust Board follow this curriculum and staff from these centres meet and share ideas to extend children’s learning. They have gardens for the children where they share and work together using traditional practices. The centres by the sea bring kaimoana to share with others. They celebrate Matariki and other celebrations important to Maniapoto and Māori as a whole, rather than Western celebrations such as Christmas. Local whānau, hapū, and iwi decide what knowledge should be available and how it should be made accessible.

Reference:

Partnering with Māori children, parents, and whānau

Key points

- Enacting Tiriti o Waitangi principles

- Improving communication, improving partnership

In a TLRI project, teachers in eleven kindergartens partnered with two academic researchers to explore ways partnerships with Māori children, parents, and whānau might be improved through better communication. This involved exploring ways of generating dialogue with children and their parents and whānau.

Teachers found that their understanding and empathy was deepened when they made time to sit and talk with parents and whānau. Whānau feedback attested that, by doing this, the centres reflected the unique place of Māori as tangata whenua and the notion of partnership inherent in Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Children, and their parents and whānau, experienced Māori ways of being and doing as normal, affirming their identities and aspirations. Whānau reported their strong sense of belonging, feeling welcomed and comfortable. The teacher-researchers in the study actively followed the principles of whanaungatanga and manaakitanga, showing concern for the wairua (spiritual wellbeing) of all those present. They realised that, for true partnership, they need to actively and deeply listen to the children, parents and whānau in their centres.

Adapted from:

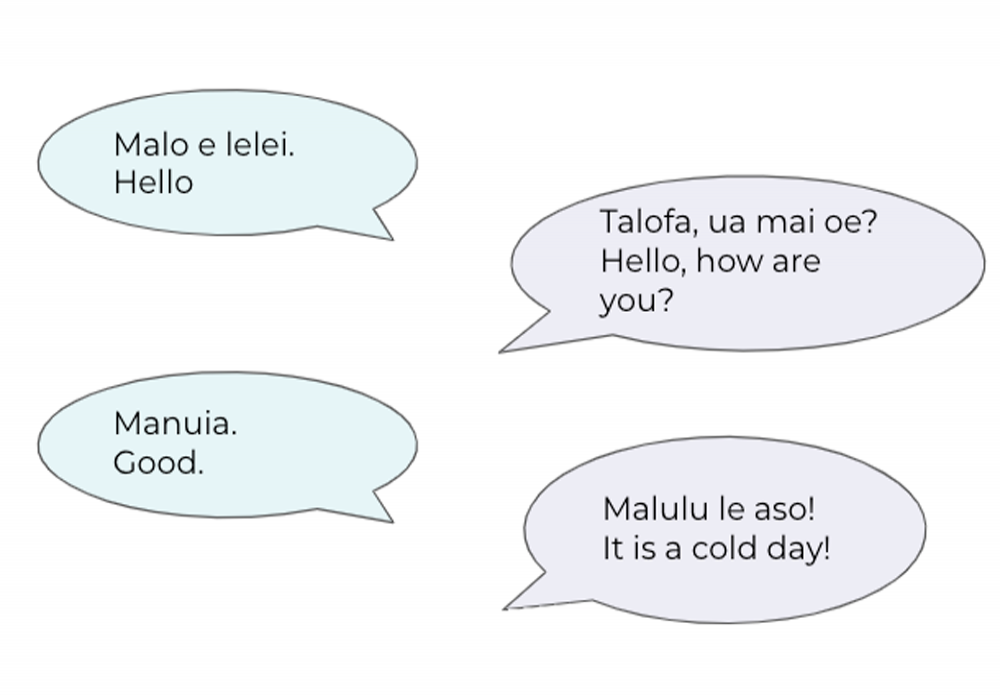

Songs from the heart – embedding Tapasā

Key points

- Kaiako learning alongside children

- Kaiako engaging authentically with Pacific families and communities

- Kaiako using Tapasā to guide their localised curriculum

Singing from the heart is a story of aganu’u, fiafia, and alofa through song.

The palagi kaiako at Netherby Merle Leask Kindergarten acknowledge the richness of Pacific cultures, values, languages, and their ways of knowing, being, and doing. These kaiako believe that what Pacific learners and their aiga bring needs to be visible, acknowledged, and celebrated as part of their localised curriculum at the kindergarten.

Kaiako were already set on their journey to engage, build, and strengthen their relationships with their Pacific learners, families, and communities. They realised that this was an on-going journey — a journey that requires a navigational compass (Tapasā). They committed to improving their practice by engaging with new ideas as well as consolidating what they had learnt already.

They began with themselves and asked, “How effectively does our teaching practice enable our Pasifika tamaiti to be successful learners?”

Working with Tapasā, the kaiako realised they had to start with their own stories and cultural narratives to better understand and “appreciate the ethnic specific identities, qualities, and contexts of each of their Pacific learners”1. Once that understanding was in place, their relationships with fanau, aiga and community flourished.

Pacific cultural symbols and languages were woven into every aspect of their pedagogy from wall displays to rich, meaningful learning stories which authentically engaged Pacific learners and their families. Pacific learners were acknowledged, celebrated, and their cultures seen, heard, and felt right throughout their kindergarten.

One Monday morning, the kaiako heard two tamaiti on the swings singing. These songs were unfamiliar to kaiako but a natural and joyous part of these two children’s culture, language, and identity. Singing often happened spontaneously at the playdough table and the kai table. They were singing from the heart! Kaiako recognised the importance of singing, including children singing their Sunday school songs, as a valued cultural experience of family, home, church, and community.

In response, kaiako were curious and asked the children to help them learn the Sunday School songs. The kaiako could already sing Pusi nofo, a favourite Samoan pese and knew that singing a Samoan pese could also be used to soothe and comfort children.

At fiafia night, an event held regularly at the kindergarten, kaiako can now join in the singing and celebrate being together with their Pacific learners and their families. What started with the children, led to their kaiako also singing from their hearts.

To begin using Tapasā you can:

- Start by knowing yourself and how your own cultural values influence your teaching

- Dig deeper to understand the cultures, languages, and identities of Pacific learners

- Be courageous and learn a word, a phrase, a song from your Pacific learners and aiga

- Work collaboratively to break down barriers and establish authentic relationships in the community

- Recognise and respect the contributions of others – make sure these can be seen, heard, and felt.

Glossary

- Aiga: Family

- Aganu’u: Culture

- Alofa: Love

- Fanau: Children

- Fiafia: Celebration

- Palagi: Non-Samoan person

- Pese: Song

- Pusi nofo: A well-known Samoan children’s song about a cat sitting on a mat

- Tamaiti: Children

Reference

1. Tapasā: Cultural competences framework for teachers of Pacific learners, page 8, (2018), Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Supporting former refugee families

Key points

- Welcoming former refugees with sensitivity

- Kaiako setting aside any assumptions and being flexible

- Proactive networking for support

Te Whāriki guides us to value the wider world of family and community and to build on the knowledge and experiences they bring.

Three former refugee families visited kaiako at Dunedin’s Brockville Kindergarten in January 2017. The families wanted to start their children at the kindergarten. They were new to New Zealand and the English language, and had a Red Cross interpreter with them. A kaiako recalls doing their best to communicate, “A cup of coffee eased the tension as I muddled my way through trying to explain the enrolment process.”

Fast forward to 2019 and kaiako have welcomed several more former refugee families to the kindergarten. Each family brings a unique set of circumstances. Kaiako revisit their understanding about family, wider community, and how to include diverse knowledge and experiences into their day-to-day practices. Kaiako have been willing to ask themselves, "why do we do what we do” and adjust planning and practices.

Nurturing family wellbeing and trust sits behind many of the small adjustments kaiako have made. For example, at enrolment time kaiako prioritise building trust over gaining information. Positive body language with hand gestures and smiles, and taking families to show them things are more effective than lots of talk.

Kaiako are careful not to jump in quickly or be insistent when a child’s approach to things is different from what they expect. They appreciate that when children arrive, it is often the little things that matter most – like keeping their bag and clothes with them at all times, or waiting until other children have left an activity before they participate. Observing and sensing when to set aside their assumptions and expectations have helped kaiako accommodate children’s needs as they settle into the kindergarten.

Kaiako have sought to foster networks and reciprocal connections with those who have first-hand experience of refugee resettlement. For example, at a workshop kaiako met Taghrid who now volunteers one day a week because she wants to become a teacher. Taghrid brings invaluable expertise in interpreting, translating, and giving cultural advice. She has helped in many ways, including translating the kindergarten’s philosophy into Arabic and reassuring a father that his child was successfully settled and learning.

Another relationship fostered with a Red Cross support worker enabled kaiako to hold a hui specifically for their former refugee families. Kaiako wrote, “We discussed development, interests, behaviour (families were very keen to know about this), and talked about food and other expectations. We wouldn’t hesitate to do this again.”

Kaiako know that they cannot always rely on others – or on Google Translate. They are therefore taking up the challenge to learn some Arabic themselves.

Promoting identity, language, and culture in a Montessori curriculum

Key points

- Making “cultural selves” visible

- Adapting Montessori for diversity

Montessori Flagstaff serves an increasingly diverse multicultural community. They are now at a point where whānau and kaiako represent approximately 14 ethnicities.

Questions about how well they were catering for this diversity were sparked by observations that several mokopuna were not accessing the curriculum as fully or as positively as they might. Kaiako had a hunch that cultural and linguistic elements were playing a part in this and that the service could do more to support the diverse identities, languages, and cultures.

The jumping off point for change became Te Tiriti o Waitangi principle of protection, in this case protection of mokopuna identity, language, and culture. Kaiako made a point of increasing their knowledge of language development through research and checking that their expectations and practices were based on sound pedagogy, guided by Te Whāriki. They also consulted parents about their priorities for their mokopuna language learning. This highlighted the importance to whānau of English language learning.

The information they gained highlighted the value of mokopuna seeing their “cultural selves” represented in the environment, and its impact on their success as learners. In response to this kaiako have:

- added culturally familiar language and resources to their traditional Montessori equipment and activities such as the Peace Corner, Grace and Courtesy presentations, and the Birthday Walk

- added books in different languages – for example, Gagana Sāmoa, Korean, Hindi, Mandarin – and encouraged mokopuna to take lead in teaching others (Ako)

- provided information for parents on the value of fostering home languages.

In observing the impact, kaiako have so far noted:

- anecdotes and stories from parents about mokopuna pride in their identity and language beyond the centre gate

- mokopuna taking books home relevant to their culture to read with their parents and returning with the confidence to teach – and sometimes correct – others, including kaiako

- some mokopuna opening up and using their home language for the first time at the centre.

Monolingual teachers in multilingual centres

Key points

- Adapting curriculum to whānau priorities

- Practical responses to increasing multilingualism

The Mangere Bridge community is culturally, linguistically, ethnically, and economically diverse. The philosophy of the kindergarten in this community highlights the importance of forging partnerships between teachers, children, whānau, and the community and the provision of an inclusive environment. At the time this TLRI research was conducted, there were 26 languages spoken in the kindergarten community, with some children confidently speaking three or more languages. Parents worked hard to sustain home languages. In the kindergarten, teachers were monolingual and spoke only English. The children communicated mostly in English but on occasion in their own home language during play.

Teachers’ practices reflected the principle of additive bilingualism, believing that parents had enrolled their child in an English-medium centre in order for their child to add English language to their home language. This approach was consistent with the kindergarten’s philosophy to work inclusively with children’s home languages and cultures to foster strong relationships.

When the research explored parents’ aspirations however, it became apparent that parents wanted their children to have support in learning multiple languages and for children to get to know and value each other’s language/s.

Teachers reflected on these findings and subsequently altered some practices. For example, they changed children’s portfolios to include spaces to prioritise the child’s language(s) and cultural identities. They also found ways to incorporate more of the children’s languages in the kindergarten, asking parents to help them learn words and phrases. They used cards and artefacts with pronunciation prompts at group times and let children show expertise by advising them on accurate pronunciation too. From these experiences, children’s heightened awareness added complexity to their understanding of difference and inclusion.

References:

Hartley, C., Rogers, P., Smith, J., & Lovatt, D., with Harvey, N., & Hedges, H. (2016). Multilingual children, monolingual teachers: Mangere Bridge Kindergarten. In V. N. Podmore, H. Hedges, P. J. Keegan, & N. Harvey (Eds.), Teachers voyaging in plurilingual seas: Young children learning through more than one language (pp. 98–115). Wellington: NZCER Press.

Reflecting a multicultural community

Key points

- Responding to changing demographics

- Strategies for intercultural exchange

Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten is a multicultural centre that reflects the changing demographics of the local community. They made the conscious decision to employ staff who share the cultural backgrounds of their community. The use of the children’s home languages and English is encouraged. Children are able to use different languages in response to the person they are talking to. Children “observing and listening” are seen as valid strategies for learning. Kaiako used this idea as a lens to analyse learning episodes and to explain learning strategies to others, finding it had particular relevance to second-language learners. They employ strategies for the intercultural exchange of ideas within the teaching team and with parents, whānau, and children, which include asking children:

- How do you feel when someone speaks to you in their own language?

- Who do you play with?

- How do you feel when you meet someone who doesn’t speak your language?

Kaiako took responsibility for finding out about family values and catering for these within their practice, identifying and using strategies when core values differed.

References:

Lees, J. (2016). One centre’s approach to supporting cross-cultural understanding and contribution. Early Childhood Folio, Vol 20, No 1, pp. 15–19.

Museums as a resource for learning

Key points

- Using public resources

- Learning bicultural heritage

Does the opportunity to interact with a range of cultural taonga deepen children’s understanding of the bicultural heritage of Aotearoa New Zealand?

This research question was explored by an early childhood setting with a prime location close to Te Papa Tongarewa, the Museum of New Zealand. This proximity enabled multiple visits to the museum and built children’s learning incrementally alongside their growing sense of pride and identity as New Zealanders, which was shared with others. Kindergarten routines and practices were rethought to incorporate more Māori concepts and rituals. Documentation of the visits and books of drawings by children have further helped strengthen understandings.

Other settings might also make use of local museums to enrich children’s learning about local history from multiple perspectives and encourage a deeper understanding of the history and partnership brought by Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Reference:

Clarkin-Phillips, J., Paki, V., Fruean, L., Armstrong, G., & Crowe, N. (2012). Exploring te ao Māori: The role of museums. Early Childhood Folio, 16(1), 10–14.

Reflective questions

Use these questions in team discussions to guide you through the process of developing and maintaining a Tiriti-based, culturally responsive curriculum.

- What are the aspirations and goals of the local iwi? How do we find out? How can the setting contribute to these?

- What do we know about the local iwi, history, and physical features of the region and the protocols, stories, celebrations, waiata, karakia, and whakataukī of the people? What more do we need to know and where can this information be found? How can we use this knowledge in practice?

- Where can the setting access support with te reo Māori? How can we use increasing amounts of te reo Māori in practice?

- In what ways do we work together to achieve the goals of the setting in terms of weaving a Tiriti-based curriculum whāriki? What else can be done?

- How does the setting’s Tiriti-based whāriki provide the foundation for all cultures to stand?

- How are we responsive to culturally diverse parent, whānau, and community aspirations and expectations for children’s learning in the setting’s whāriki?

- How do we find out what supports a sense of belonging for all children and their parents and whānau?

- In what ways do the environments and practices in the setting reflect the identities, languages, and cultures of the children who attend?

- How might we work with tensions that can arise between differing cultural norms, roles, responsibilities, and rituals?

Implications for leadership

One of the most significant implications for pedagogical leadership is the “how to” of weaving a Tiriti-based curriculum whāriki that provides the foundation in which to affirm and strengthen the identities, languages, and cultures of all of the children, whānau, kaiako, and communities of the ECE setting.

A Tiriti-based curriculum that truly reflects the cultural context of Aotearoa New Zealand is one where te reo Māori, tikanga Māori, and an understanding of Māori perspectives is clearly visible. Leaders need to support kaiako to draw on and use a range of knowledge, strategies, and practices, including:

developing reciprocal relationships with Māori iwi and communities

- implementing respectful practices

- engaging in independent research and inquiry

- using te reo Māori whenever and wherever possible

- working collaboratively to achieve their aspirations.

This may require accessing professional learning and development opportunities.

A thoughtful leader will facilitate the development of an overarching strategy to increase the use of te reo Māori and guide other adults to envision a whāriki for their setting where a Tiriti-based curriculum is implemented.

The increasing complexities and diversity of families in Aotearoa requires consideration and reflection by leaders to ensure all whānau identities, languages, and cultures are visible and supported. Kaiako can engage with communities, including participation in cultural events, strengthening relationships, knowledge, and understanding. Engaging in research and inquiry will also help kaiako gain a better understanding of the children, families, and communities of their setting, and their backgrounds. Leaders should ensure that curriculum experiences and resources are sensitive and responsive to the different cultures and heritages among the families of the children attending that service.

The provision of respectful, responsive practices may include initiating celebrations, sharing food, and projects that focus on the values and stories of their communities. Using community languages in the ECE setting acknowledges Te Whāriki as "a place for all to stand".

Connections to principles

Empowerment – Whakamana

Promoting and protecting the mana of children is critical to their learning and development. The ways in which whakamana is understood and reflected is embedded within cultural perspectives and the ways these perspectives are expressed. By respectfully acknowledging and being responsive to the identities, languages, and cultures of the children who attend their services, kaiako create an environment where children develop self-esteem and confidence about who they are and their place in the world.

Family and Community – Whānau Tangata

The identities, languages, and cultures of whānau and communities influence child-rearing patterns, beliefs and traditions, and the ways different knowledge, skills, and attitudes are valued. Children’s learning and development is enhanced when there are connections across the settings in their lives, including their homes. Fostering culturally and linguistically appropriate ways of communicating with whānau, parents, extended family, and community is an important feature of this connectivity.

Holistic Development – Kotahitanga

Identities, languages, and cultures are important aspects of children’s lives and their relationships with their worlds and others. Cultural understandings influence perceptions of the cognitive, social, cultural, physical, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of human development. The ways in which these dimensions of children’s lives are interwoven is therefore shaped by the identities, languages, and cultures of children, whānau, and kaiako.

Relationships – Ngā Hononga

The development of culturally and linguistically appropriate ways of communicating with parents, whānau, and community supports the development of meaningful, trusting relationships. These relationships may acknowledge the past, present, and future, the importance of place and land, and engagement with people, places, events, and taonga. It also requires understandings of, and respect for, whānau aspirations for their children.

-

Useful resources

This review of the literature highlights and clarifies key evidence towards improved learning and achievement outcomes for Pasifika learners and identifies priorities for future research in Pasifika education.

This article reports on a qualitative, interpretivist project. Findings related to a Pasifika child are presented. The child’s overt interest in drumming led to deeper examination of his developing identities as a learner and member of his family and culture.

Learning wisdom: Young children and teachers recognising the learning

This project aimed to explore the ways in which young children could become more wise about their learning journeys, and perhaps the learning journeys of others.

Ngā taonga whakaako: Bicultural competence in early childhood education

A review of literature on bicultural curricula and Māori education developments in New Zealand, and a study of New Zealand early childhood education practitioners' perceptions of bicultural knowledge, practices, theory, resources, and professional development, based on surveys, interviews, and focus groups with 214 teachers and teacher educators.

Pacific identities and well-being: Cross cultural perspectives

An anthology addressing the mental health and therapeutic needs of Pacific and Melanesian people.

Agee, M., McIntosh, T., Culbertson, P, & ‘Ofa Makasiale, C. (Eds.) (2013). Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Press.

Guidelines:

- Ta'iala mo le Gagana Sāmoa – The Samoan Language Guidelines

- Gagana Tokelau – The Tokelau Language Guidelines

- Ko e Fakahinohino ki he Lea Faka-Tonga – The Tongan Language Guidelines

- Tau Hatakiaga ma e Vagahau Niue – The Niue Language Guidelines

- Te Kaveinga o te reo Māori Kūki 'Āirani – The Cook Islands Māori Language Guidelines

Perspectives on early childhood education: Āta Kitea Te Pae – Scanning the Horizon

This book outlines the many diverse perspectives on early childhood teaching and learning in Aotearoa New Zealand and provides an overview of developmental theories. Each chapter in this book deals with one aspect of the early childhood landscape, while reflecting the perspectives of the various authors involved.

This article reports on a Pasifika child’s interests from a current Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) project. Understandings were informed by his family’s and teachers’ perspectives, theories such as funds of knowledge, and a typology of teachers’ thinking about student identity.

Teaching and learning in culturally diverse early childhood settings

This qualitative study aimed to generate an exploration and analysis of culturally responsive teaching and learning in three diverse education and care centres.

Te Whariki: Early childhood curriculum from Samoan teachers perspective

A master’s thesis. Salilo Ward interviewed Samoan teachers from two ELSs about their experience of implementing Te Whāriki through a Samoan lens.

The New Zealand Curriculum Online

Thinking otherwise: ‘Bicultural’ hybridities in early childhood education in Aotearoa/New Zealand

In this article, Jenny Ritchie profiles narratives from three teachers as they take different paths navigating what it means for work within a bicultural curriculum.

Whakawhanaungatanga: partnerships in bicultural development in early childhood education

This TLRI project utilised collaborative partnerships between teacher educators, professional development providers, and early childhood educators, in order to identify effective strategies for building and strengthening relationships between early childhood educators and whānau/hapū/iwi Māori within ELSs.

Supporting former refugee families

Resources to help build knowledge and experience for working with former refugee families: